Corner Brook Artist Confronts Colonialism’s Im/Permanency

In “Fire Creates its Own Wind,” Melissa Tremblett moves beyond reclamation and creates a space for hard discussions.

Justin Brake, The Independent, 2022

Melissa Tremblett speaks at the July 20 opening of her new show,

“Fire Creates its own Wind.” Photo by: Sampson Vassallo / Courtesy Grenfell Art Gallery.

Colonialism doesn’t just go away—it’s something you live with. And that’s not easy, Melissa Tremblett will tell you.

It also takes on many forms, reaching from one generation into the next in lurid and subtle ways. And it’s both personal, and political.

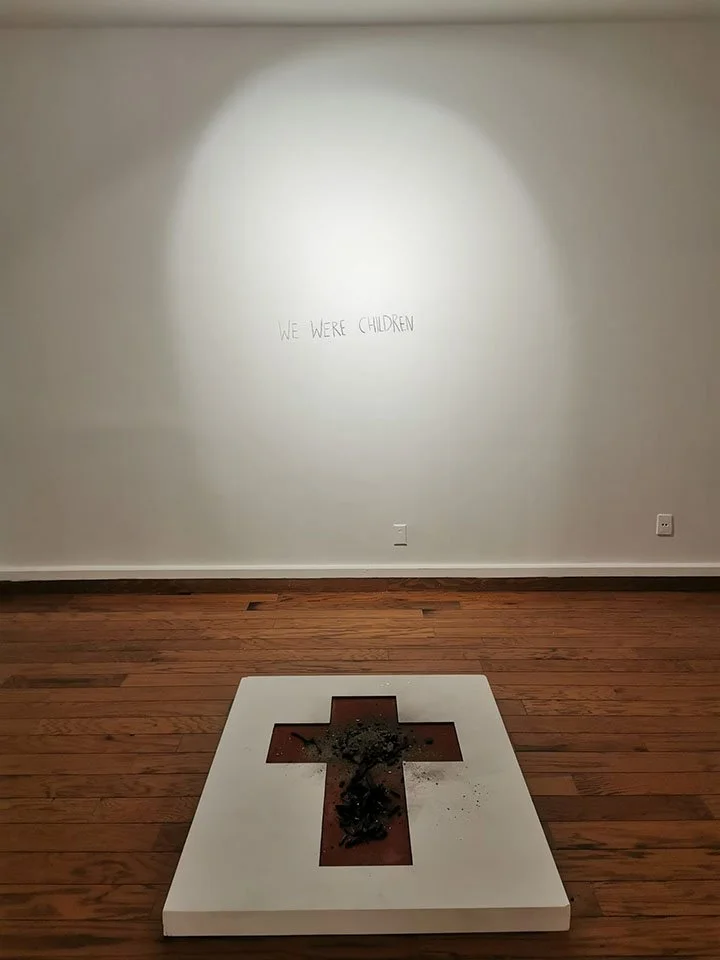

In Tremblett’s latest show, colonialism resides in a pile of ashes atop a red cross engraved into a plinth.

Nearby, a video projected onto the wall provides the images and sounds of wood burning in a crackling fire, bringing you a bit closer to what it might be like to take on a ghost so old and large that one wonders if it can ever be defeated.

But it’s not the Corner Brook artist’s first rodeo confronting the colonialism that pervades her life. Her new exhibit at the Grenfell Art Gallery is just her latest creation in a battle she knows she may never win.

An Act of Reclamation

In 2019, Tremblett turned a moment of personal courage and reclamation into an important act of healing.

She was in Banff for the Ghost Days Artist Residency—a unique opportunity for artists “to conjure spirits and ghosts as audience and collaborators,” the project’s Facebook page explains.

One night, the Labrador-born artist decided to confront the ghosts of colonialism in her life.

While studying Fine Arts at Grenfell in 2013, Tremblett took two self-portraits that were, at the time, “shocking” because they marked the first occasion she’d turned the camera on herself, she recalls.

She felt vulnerable then, as she did in Banff when she photographed herself once more. Yet, much had changed.

Backlit with colour-filtered Playskool brand flashlights, Tremblett captured ghostly images of her body and essence that bespeak an intentionality and confidence their predecessors do not.

She called the new ones, “Reclaim.” They embody the wholeness of Tremblett’s journey both in the intervening four years and from the very beginning.

“All of the parts of myself are just who I am right now,” she says during an interview with The Independent, standing before the larger-than-life photographs displayed on the gallery’s walls.

The toy flashlight “excites the child in me,” she says, while the black and white images show “how far I’ve come.

“I love them and celebrate them,” she adds. “They are beautiful and powerful.”

But senses of beauty and power can be elusive for Indigenous people. They are two things that successive settler governments have tried to legislate out of existence.

1876 Changed My Life

Tremblett’s father hails from Sheshatshiu Innu First Nation. Her mother is from St. John’s. In her youth, until she was 18, Tremblett split her time between the reserve community and the island towns to which she moved around.

In Sheshatshiu, she was often viewed as an outsider. And in the island’s white communities, she never felt a sense of belonging.

Her relatives attended a residential school in North West River, an event she points to as a source of trauma in her family.

It “led to the hurt in the communities, that led to the intergenerational trauma, the way my grandparents parented my father’s relatives, which in turn affected how my father parented me,” she says, explaining the “social family connections [and] emotional connections” at the core of Innu society were disrupted.

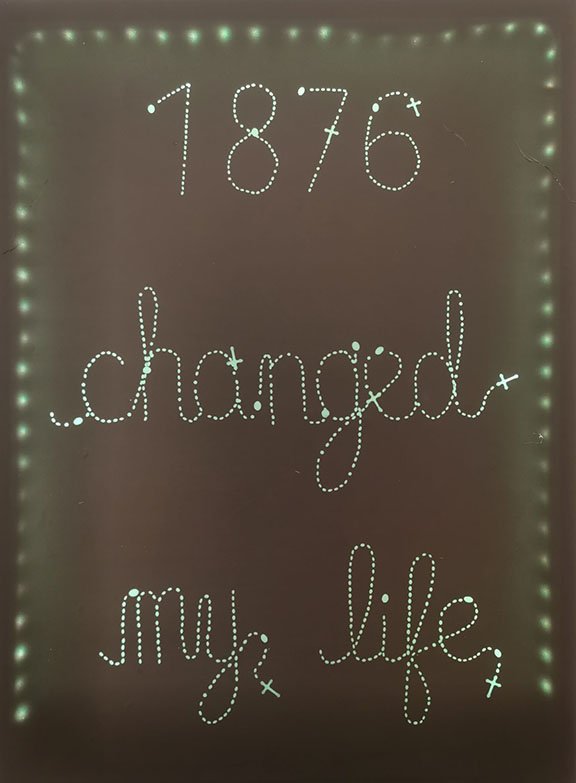

The impacts of residential schools and other forms of legislated state violence and genocide against her ancestors, her relatives, and herself were the focal point of Tremblett’s 2017 show “1876 Changed My Life” at the Rotary Arts Centre’s Tina Dolter Gallery in Corner Brook.

In 1876, Canada introduced the Indian Act as part of the new country’s campaign to assimilate and exterminate the hundreds of First Nations tribes whose lands European settlers desired.

For the installation, Tremblett made Innu tea dolls but instead used a pencil to stuff them with a shredded copy of the Indian Act.

“I had to keep pushing and pushing and pushing until [each doll] was completely full. And same with the heads—I had to fill them with the Indian Act,” she says, still disturbed by the thought.

Tremblett’s show “1876 Changed My Life” explored the ways Canadian government policies created intergenerational trauma in Indigenous Peoples’ lives. Photo by: Justin Brake.

It was the first time she’d made the dolls; a skill her grandmother passed on. It was both “spiritual and cultural,” she explains. Then, Tremblett laid the dolls in white wooden cribs she constructed to mimic those often used in the largely church-run institutions. “I cut off their hair like they would have in residential schools. Indigenous people always had long hair—there was power in hair, there was creation, there was connection to the ancestors. So to cut that off—and I had to be the one to do that—I just sat there and cried and it was awful.”

Tremblett says a lot of her work is “about processing things,” and 1876 Changed My Life was just that.

But not only for her. For willing settlers, too.

“That was the moment where people had to consider for themselves what was going on,” she says, explaining some of the dolls had blankets over their heads, leaving the observer to wonder whether they were hiding from abuse, sleeping, or dead. Glow in the dark rosary beads hung over their cribs, where mobiles might for non-Indigenous babies.

“They represented what the kids had to look forward to—to addiction, to destruction, to what the colonial project was all about: hate, disdain and loss of culture.”

At the time, Canada’s 150th anniversary celebrations were just around the corner, and Tremblett was compelled to stage her own intervention.

The “celebration of settler culture, and only seeing the good” of Canada while not adequately recognizing the atrocities on which the country was founded, she says, moved her to action.

After the Photo

After the 2019 self-portraits, while still in Banff, Tremblett documented another critical step in her journey. She held a ceremony, inviting her peers to braid her hair, talk about it, and then cut it off.

“Each person cut off their braid and they got to keep it,” she recalls. Then, the residency’s facilitator, Terrance Houle, gifted Tremblett a braid of sweetgrass the exact same length of the braid that she kept for herself, “which I thought was really beautiful,” she says.

The hair and sweetgrass now sit side by side on the wall between Tremblett’s “Reclaim” portraits.

There’s a trajectory to Tremblett’s work. And while the new exhibit, “fire creates its own wind,” represents a chronology of events, the works, new and old, also weave together themes of permanency and change, decolonization, and inner contradiction and conflict.

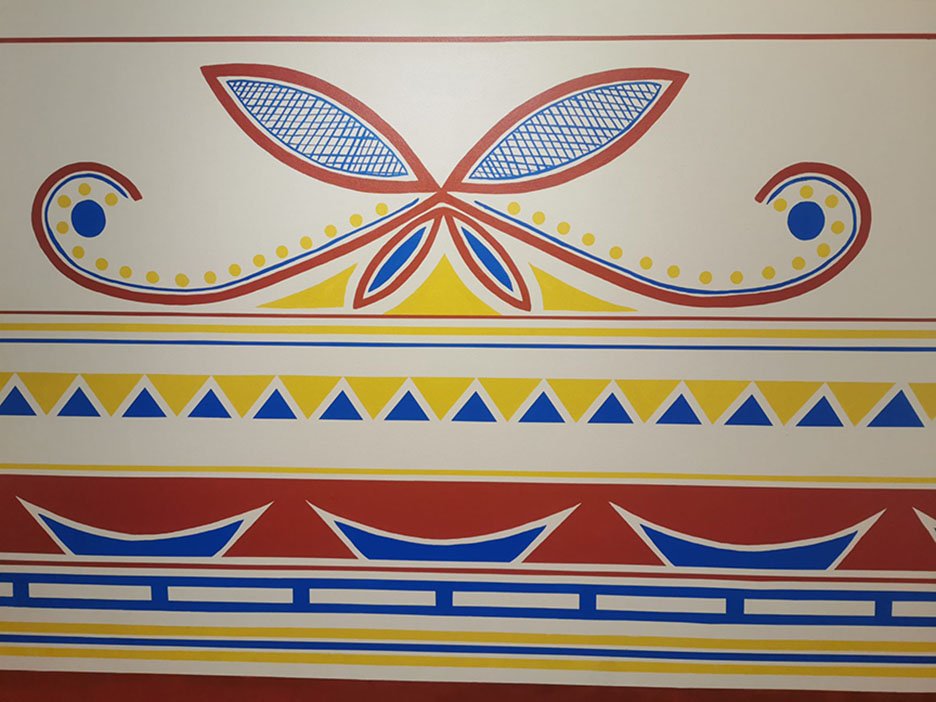

Visitors to the gallery are greeted by a large wall mural inspired by motifs from Innu caribou coats. Citing inspiration from Dorothy Burnham’s book “To Please the Caribou,” a collection of images of caribou-skin coats worn by Innu and Cree hunters of the Quebec-Labrador Peninsula, Tremblett says drawing motifs is her way of learning about Innu history and culture “in a way that’s visual and that I can understand, because I can’t understand the language.”

But she doesn’t take drawing them lightly. When it came time to paint the mural as a new piece to feature in her show, Tremblett wanted Burnham’s book for inspiration—but she couldn’t find it. She searched the internet for Innu motifs but couldn’t find images of the same quality and detail. So she created the design based on “little snippets that I could get from other places,” she says, adding the rest “came from the heart—it came from the ancestors.”

She doesn’t paint much, “because I don’t feel an emotional connection” to the practice. But when it came time to create the mural, “I just started painting,” she says. Once she began, she told herself “there’s no going back now.”

“It was really nice to just sit there and be here in this space alone, really thinking about it.” She says she was “nervous about starting—maybe about claiming my culture,” but in the process she became “more steady with my hands and I was more confident with the marks that I was making.”

“This is my artistic interpretation of my culture, seen through the lens of my experience,” she says, looking at the mural.

This mural greets visitors to the Grenfell Art Gallery. Photo by: Justin Brake.

Processing

After 1876 Changed My Life wrapped, Tremblett stored the cribs in her home, moving them from room to room “because they were always in the way.”

Then, her husband Jason had an idea: burn them.

Tremblett was hesitant because she had been invited to show them elsewhere. She didn’t want to say no to opportunities that could advance her career as an artist, but at the same time, she “never felt comfortable with it.”

Then she realized the 1876 installation “is done and will never exist in the context that it did,” she says.

“I don’t need to put that energy out into the world anymore. I have documentation of it, I can talk about it. And so I did burn them,” she says. That burning ceremony is captured in the video projected on the wall of her new show. The resulting ashes and charcoal “can be given their own life—so the legacy of that piece itself still carries on, just in a different form.”

They are the ashes and charcoal resting in heaping piles atop the red cross on the plinth, just around the corner from Tremblett’s mural. The juxtaposition is deliberate, between the mural’s bright red, blue, and yellow colours that represent a vibrant Innu hunting culture, and the deeper red of the ash-covered cross.

The installment was inspired by the ongoing discoveries of suspected unmarked graves at former residential school sites across the country. “It was something that created itself in a way,” Tremblett explains. “I made it happen, but it needed to be here.”

One day, during the show’s setup, she was in the gallery with a single piece of the charcoal in her hand, trying to figure out how to create the piece. “I just walked to the wall and I wrote ‘We were children,’ and then I sat on the floor and I cried.”

The piece represents a key part of reclaiming her Innu identity, Tremblett says, and of “reclaiming myself as a confident person in my body now, in my mind now—being able to process those things and putting it out to the world and saying I want to talk about it, I want people to talk about it.”

This piece was inspired by the continued discovery of suspected unmarked graves across Canada.

Photo by: Justin Brake.

From the Ashes

In every moment or place where Tremblett didn’t feel belonging, she created the space to say something—addressing themes and topics that many don’t, won’t, or can’t talk about. But in the process she is forging the self-assurance and kinship that might exist if it weren’t for the violence of colonialism.

In a way, she’s creating a new reality for herself, and at least in some small respects, for others.

The phrase “fire creates its own wind” came from something a friend of Tremblett’s said while sitting around a fire years ago. “For some reason it really stuck with me,” she says.

“When it came to this show, it’s about resurgence, it’s about natural growth. Although fire causes a lot of destruction it also creates new beginnings. But fire also creates its own wind in that it needs stuff fed to it in order for it to grow, in order for it to thrive,” she explains.

“Where I am right now in my practice, I’m getting so much support from other Indigenous people and people in other institutions. Not that I can’t go on my own but […] the support I’ve been getting from people across Turtle Island, it gives me that wind and fuels this fire. I haven’t created work in a long time, so having this out and seeing my journey, it’s just creating this new resurgence of pride, of my art practice.”

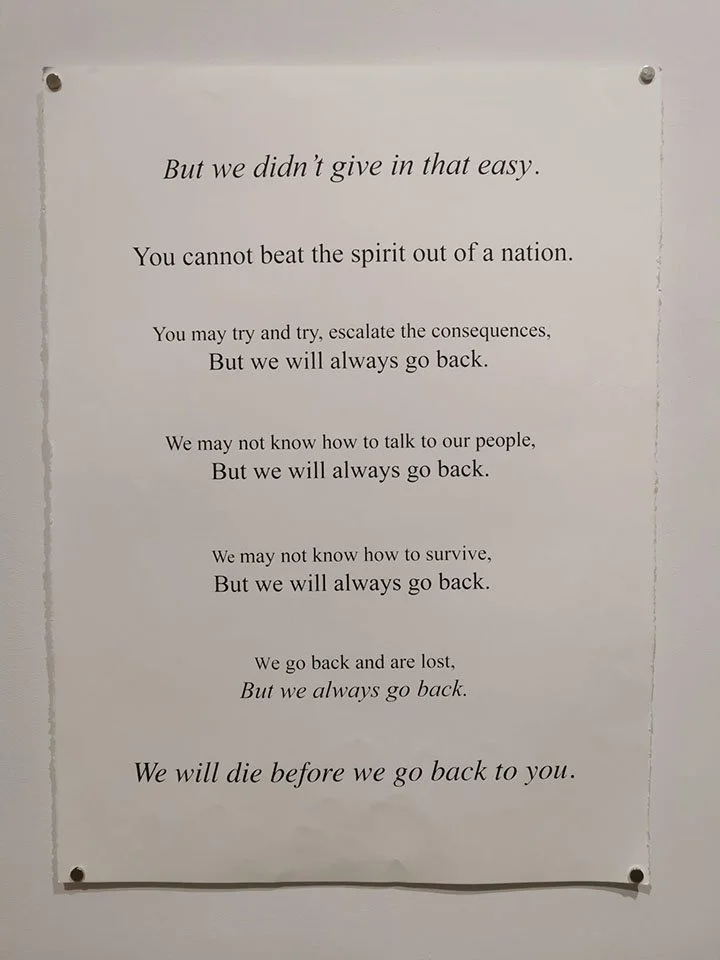

Tremblett also turned some of her writing on colonialism into an art piece. Photo by: Justin Brake.